Alaska Native Performance

Toksook Bay, Alaska

“You could call Thomas Riccio a citizen of the world. But his world is the little-known world of indigenous

peoples, pushed aside by industrialization; and his language is the theater, whether he is in the Kalahari

Desert, Siberia or back home in Fairbanks, Alaska.

Riccio grew up in Cleveland and graduated in 1978 from Cleveland State University, where he became active

in theater. After graduate school in Boston and New York, he came back in 1985-86 to be dramaturge at the

Cleveland Play House. When he left to become artistic director of the Organic Theater in Chicago, it looked as

if he were headed for a career making cutting-edge theater.

But in 1988, he left Chicago to teach theater at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. And from there, he has

launched an extraordinary career helping native peoples reclaim their cultures through theater.”

Archival

“These semi-subterranean structures had several tiers of hide-covered benches that created a three-sided or theatre-in-the-round stage setting. During some performances a central fire pit would throw off a powerful light and produce large and looming shadows on the soot covered driftwood, hide and earth structure. During some performances, when the fire pit was covered with planks, seal oil lamps provided an equally dramatic source of light. There were two tunnel entrances used to keep the arctic weather out, one entrance was for general public use the other tunnel entrance was connected to the fire pit and provided a draft for the fire. Through the fire pit entrance, performers and shamans would enter, for it was thought that the fire pit tunnel was a pathway to the lower world. Spectacular entrances were made from the skylight or smoke hole, thought to be an entrance from the upper world. The upper and lower worlds were thought to be places where certain spirits dwelled, and where spirits were aligned more with the elements and hierarchy rather than with the heaven and hell connotations of Christianity. In this way the kashim, or community house, became a living metaphor. The community, gathered tightly together in an earth structure, was acted upon by the spirits from above, below and within the shadows of the fire flames. (Curtis, 1930:9-12) ”

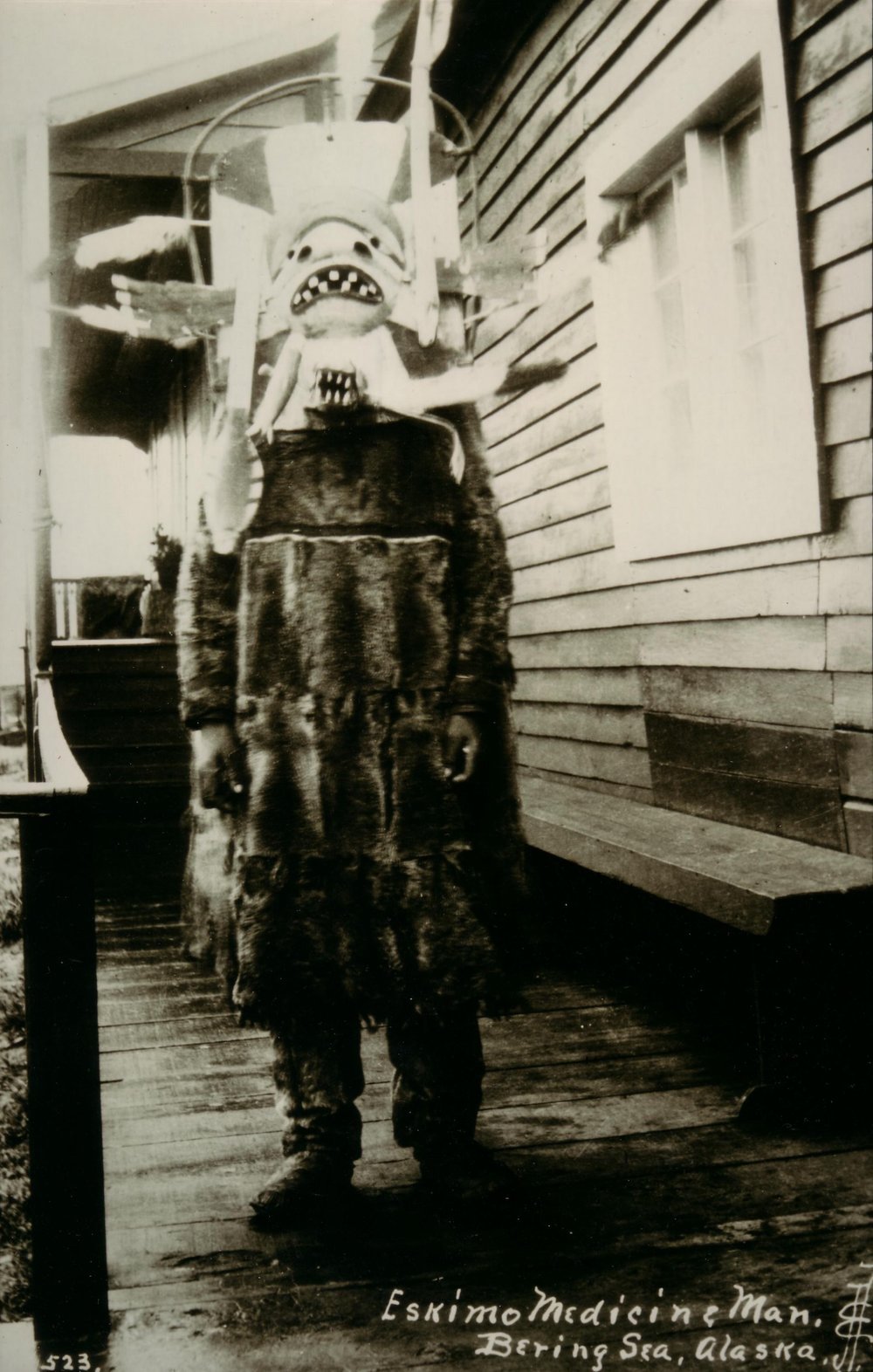

Yup’ik Shaman

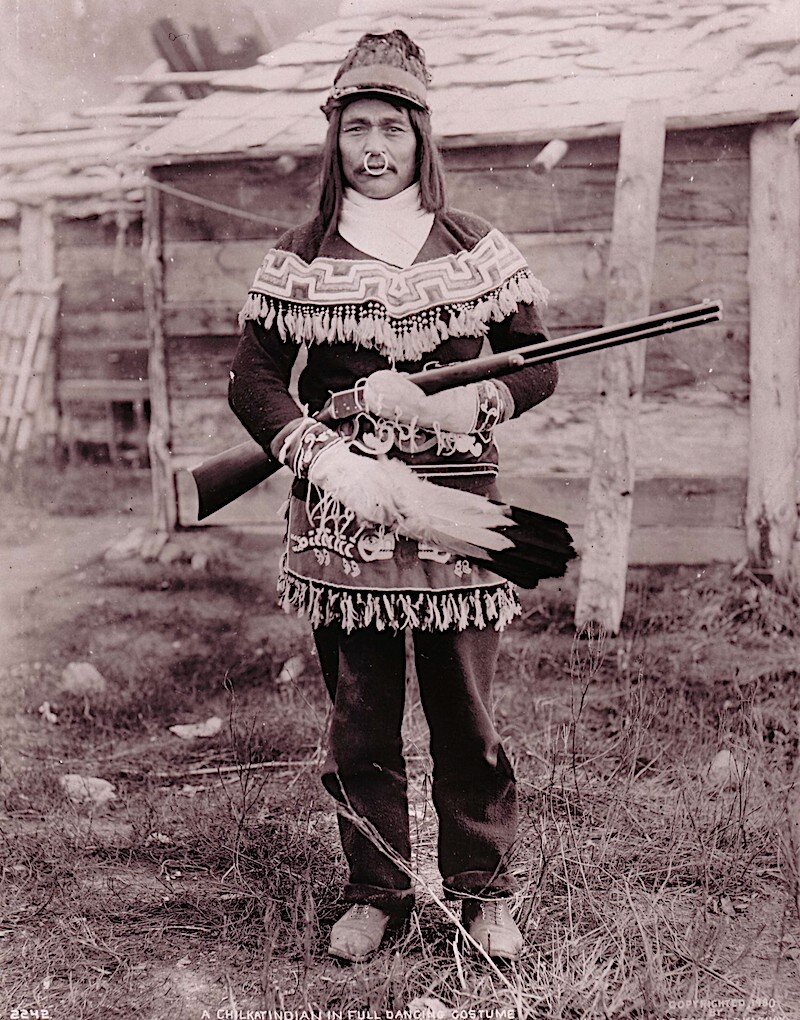

Kiviq, Eagle-Wolf Messenger Feast , circa 1890s

Yup'ik and Inupiat Traditional Masks

Puffin Beak gloves, used in Kiviq ritual

Inupiat grave masks

“Central to the Alaskan Eskimo theatre tradition were the elders and the angatkok. The elders were the holders and conveyers of tradition in every aspect of Eskimo life. From generation to generation, performance stories, songs, dances, acting, props, costumes and mask traditions were passed on with adjustments and evolutions taking place over time. The elders kept their orally transmitted theatre tradition alive; it was a tradition that could lead back several centuries.

In most theatre performances, the elders worked in conjunction with the angatkok, the shaman, the healer, the medicine man or woman, the keeper of the community’s spiritual well-being. The angatkok was variously chosen, trained or called into their position because of special expressed attributes, which generally included spiritual vision. The calling of the angatkok was a gift, something that came to a person naturally or something a person sought to obtain and develop because with it came power and responsibility: a responsibility to the community’s very survival and power to affect physical and spiritual well-being. The angatkok was responsible for improving the weather, healing the sick, procuring games, foretelling the future, contending with evil spirits. All of the angatkok’s activities were performed in public and with the community’s interaction, for the role of the angatkok was, at its core, that of a performance artist. The performance of the angatkok reassured the community by demonstrating that there was indeed interaction between the human and spirit world and that decisive action was being taken. The angatkok’s performance, trance, dance, vocalizations, or ritual was a bridge to a mysterious and ineffable world to the community. Like the secular theatre artist of the Western tradition, the angatkok gave form and feeling to the intangible ideas and spirits surrounding and living with the community. ””

Contemporary

Inupiiq Kiviq, 2017, Barrow, Alaska, photos: Bill Hess

The theatre of the Alaskan Eskimo was a theatre of visions and myths and functioned in a time when the world was a shroud of mystery filled with spirits. It was a theatre tradition that originated in the time before time. It was a time when humans could easily transform into animals and animals into humans. When myths were formulating the earth's shape and its ways. A millennium before Aristotle's Poetics, this was a theatre of the earth, for those who lived by, off of and with the earth. And like the earth was practiced as a dynamically changing medium of performance expression. The theatre of the Alaskan Eskimo was a theatre of the land, its elements and the animals and humans that inhabited that reality. It was a theatre interlinked to its culture as only aboriginal performance can be; separate but inseparable, a part, but of the whole.

from

Traditional Alaskan Eskimo Theatre: Performing the Spirits of the Earth